This is an ongoing sporadic series, in which I explore classic fantasy and science fiction works. Appendix N is the bibliography of Gary Gygax's original Dungeon Masters Guide, and lists a range of classic SF and fantasy authors that influenced his interest in the fantastical. See the first part of this series for more information.

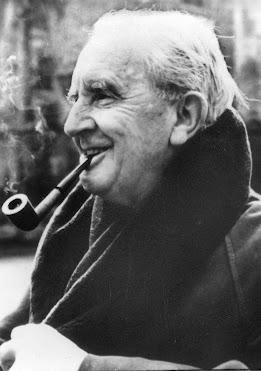

JRR Tolkien

Of all the people on this list, Tolkien probably requires the least introduction. He’s one of only a handful of British authors in the Appendix N, but arguably the grandfather of modern fantasy. Born in Bloemfontain, South Africa, in 1892, but grew up in the Midlands in the UK, serving in the First World War and eventually becoming Professor of English Language and Literature at Merton College, Oxford. Tolkien later retired to the coastal town of Bournemouth using the proceedings from Lord of the Rings. Tolkien specialised in Anglo-Saxon, and one of his more scholarly publications is a translation of Beowulf, which he apparently used to declaim loudly in the original Anglo-Saxon when he entered his lectures.

There are various events in Tolkien’s life that inform some of the elements in his fantasy books, but a lot of it also comes from his love of constructed languages, and his desire to weave elements from Norse and Germanic myths into a mythology for England.

The Hobbit

Tolkien began The Hobbit during the 1930s; according to Brian Sibley’s biography he spotted a hole in the carpet of his college rooms and idly wrote the famous opening line - “In a hole in the ground there lived a Hobbit”, before his later ponderings on what a “hobbit” actually was led him to write his adventure story.

We know the plot by now, don’t we? Bilbo Baggins, the hobbit in question, is plucked from his cosy bucolic life of an independently wealthy country squire by the wizard Gandalf and a band of dwarves led by Thorin Oakenshield with the goal of trekking across Middle Earth to reclaim the land and wealth stolen from Thorin’s ancestors by the dragon Smaug. (Later ret-conning by Tolkien found in the Lost Tales series suggest that Gandalf had orchestrated the whole endeavour to remove Smaug as a chess-piece from the forces of Sauron prior to the War of the Ring, and to create a stable nation in the north-east Wildlands region).

The story is largely a sequence of disparate events, encounters with trolls, elves, goblins, the creature Gollum, wolves, spiders, giant eagles, the were-bear Beorn, more elves, the Men of Lake Town until finally the quest reaches their goal of the Lonely Mountain and the narrative becomes more connected, anchored around the dragon, his lair, and his hoard. Like The Blues Brothers, everybody that Bilbo and the Dwarves have annoyed on their journey pursues them to a final climactic showdown.

Because this is written primarily with a younger audience in mind, the lore and songs are kept to a minimum and are lighter-hearted for the most part compared to Lord of the Rings, and each chapter is relatively self-contained, with trickery and/or luck providing the solution – keeping the trolls arguing until the dawn sun turns them to stone, for example, or a riddle contest with Gollum. Gandalf even pulls the same trick of drip-feeding the dwarves on both Bilbo and Beorn. Apart from the driven Thorin, the young and eager Fili and Kili, and Balin who provides Bilbo with a staunch ally among the dwarves, the rest of them have little in the way of personality, being more of a homogenous blob (apart from Bombur whose defining characteristic is being overweight). This is one area where the Peter Jackson films improved it, providing at least a visual clustering of the dwarves – the film’s propensity to turn everything into an extended action sequence counting against them in my opinion, but then this is a book, not a film review.

The light-hearted discursive, and fourth-wall breaking tone of The Hobbit is also a characteristic and makes it a fun book to read despite its length and breadth. And as a child, the idea of not only a map but runes that you the reader are left to decipher were great fun.

The Lord of the Rings

Pressed by the publishers Unwin to produce a sequel to The Hobbit, Tolkien scraped together some other ideas that he’d had, with the initial inclination to do something similar in tone. But this slowly and gradually grew, writing on scraps and margins during the wartime shortages, and the work began to borrow more and more from his constructed languages and mythologies. I suspect, although Tolkien himself denies, that the darker times of WWII influenced the darker tone of Lord of the Rings. I also like to think that the lighter tone of the earlier chapters, similar to The Hobbit, are those parts of the Red Book written by Bilbo, with Frodo having a more serious and arch writing style as seen in the later chapters.

Plotwise, does anybody need me to spell it out? We begin with A Long-Expected Party to counter the Unexpected Party at the start of The Hobbit. Gandalf returns to The Shire to visit his old friend Bilbo, now 111 years old and still looking young. This, Gandalf suspects, is due to the magic ring that Bilbo “won” from Gollum, which he persuades Bilbo to entrust to his nephew and heir, Frodo Baggins.

As it transpires, the ring is The Ring, forged by the Dark Lord Sauron as a means to sustain his life and to wield dominance over all. Its very presence corrupts lesser mortals and its existence ensures that Sauron can never be truly destroyed, despite having been defeated thousands of years ago. As with The Hobbit, the story starts as a travelogue, with Frodo, his manservant Sam, and his two cousins Merry and Pippin, fleeing across the Shire pursued by sinister men in black (whom we later discover are great kings of men enslaved to the Ring as Ringwraiths); and for these sections Tolkien very ably takes the safe and comfortable and inserts a terrifying menace to it.

Eventually the hobbits reach Rivendell, aided by the ranger Strider, but not without Frodo taking a terrible wound. At the Infodump of Elrond, we learn more about the history of the Ring, current events in Middle Earth, how Gandalf’s superior Saruman has joined with Sauron, and how to destroy the Ring. Frodo volunteers to do it, since nobody else seems willing nor capable, and he is accompanied by his hobbit friends, Gandalf, Strider (revealed as Aragorn, heir to a long-lost line of kings), Boromir from the city of Gondor on the frontlines against Sauron, the elf Legolas and the dwarf Gimli (son of Gloin, one of Bilbo’s companions).

More set–pieces follow as the Fellowship head south; be-snowed in the mountains, the classic atmospheric journey through the abandoned dwarf kingdom of Moria and the climactic encounter with the demonic Balrog in which Gandalf seemingly dies, through the elf woods of Lothlorien and down the River Anduin, leading to a deciding moment where Boromir becomes tempted by the Ring and forces Frodo to set off alone (with Sam).

Boromir redeems himself by defending Merry and Pippin against some Uruk-Hai sent by Saruman, dying in the attempt. With Frodo and Sam heading off to Mordor alone, Merry and Pippin captured, and Boromir dead, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli choose to try to rescue Merry and Pippin, and the story splits into multiple narratives. Tolkien manages, however, to weave together the different strands with considerably more economy than modern authors such as Robert Jordan or George RR Martin, both of whom suffer from plotline/character bloat.

From here-on, the story essentially follows either Frodo and Sam as they make the lengthy trek to Mordor, through swamps, encounters with Boromir’s altogether more noble younger brother Faramir, through the lair of the giant spider Shelob, all led by a treacherous Gollum. Meanwhile, to the west, Merry and Pippin escape their captors and meet Treebeard the Ent, a shepherd of the forest who is roused to anger against Saruman thanks to Saruman's despoliation of his forests. Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli, in pursuit of the hobbits, learn that Gandalf has returned as Gandalf the White, and end up embroiled in the struggles of Rohan, a nation where Tolkien gives his beloved Anglo-Saxons some horses to ride.

There are seiges, and then greater seiges, there are last-minute rescues, there are giant elephants, a great turn for the Rohirrim lady Eowyn, and a lengthy denouement wherein we learn that evil is never quite destroyed. Tolkien entertained the idea of the “eucatastrophe”, a sudden and unexpected turn for good, rather than ill, and he makes good use of it.

While critics accuse Tolkien of being turgid, I’ve never really found him so. He likes to throw in lots of songs and lore from his work on the mythology of the world, published posthumously as The Silmarillion. As the book goes on, especially when dealing with Men rather than Hobbits, he tends towards a very formalised, King James Bible manner of speaking. But elsewhere his characters have a pleasing level of depth – the humble loyalty of Sam, the duplicity of Gollum (who craves and hates the Ring with the fervour of an addict), even the amusing friendly rivalry between Legolas and Gimli. Foremost of the characters, however, is the world itself, described in relentless but glowing detail.

The overall story may be more densely packed with characters, and follow more of an extended narrative, than the more swords-and-sorcery offerings in the Appendix, but it’s also more rewarding for it. And compared to modern fantasy sagas, it’s tiny, taking up about the same number of pages as a single book in the Wheel of Time or Song of Ice and Fire sagas.

Inspirations

Tolkien has a strange place in terms of inspirations. The elves, dwarves and orcs follow Tolkien the most closely than other fantasy/folklore iterations. Halflings, treants, and the Balor demon are product-identity dodging hobbits, ents, and Balrog respectively. Arguably, giant eagles, the werebear, worgs, giant spiders, stone giants, and wights all get their inspiration from Tolkien too (but could equally come from the same kind of folklore). And the Ranger class, of course, is clearly inspired by Aragorn (and Faramir); back in the 1st Edition when every level of a character class had a title, the Ranger class had a level called Strider.

And yet, the story is a terrible model for a D&D adventure; far too much need to railroad (see the DM of the Rings webcomic for more - its creator Shamus Young having sadly passed away). Epic Quests are fine, but it’s the swords-and-sorcery stuff that plays more like a D&D game. Adventurers are usually more Conan, Kyrik, Cugel, Fafhrd or Grey Mouser than they are Frodo and Sam. The success of Lord of the Rings spawned endless trilogies of quests against a Dark Lord (Shannara, for example), and most don’t come close. Tolkien also brings a massive amount of lore to bear behind his writing which, as a DM, is not always advisable – it's a lot of work for little gain. Better to have dabs and dashes of lore rather than worry about having languages and poems and history and onomastic myths fully mapped out for everything; you’d kill yourself.

As stories, though, they reward close attention.

There are seiges, and then greater seiges, there are last-minute rescues, there are giant elephants, a great turn for the Rohirrim lady Eowyn, and a lengthy denouement wherein we learn that evil is never quite destroyed. Tolkien entertained the idea of the “eucatastrophe”, a sudden and unexpected turn for good, rather than ill, and he makes good use of it.

While critics accuse Tolkien of being turgid, I’ve never really found him so. He likes to throw in lots of songs and lore from his work on the mythology of the world, published posthumously as The Silmarillion. As the book goes on, especially when dealing with Men rather than Hobbits, he tends towards a very formalised, King James Bible manner of speaking. But elsewhere his characters have a pleasing level of depth – the humble loyalty of Sam, the duplicity of Gollum (who craves and hates the Ring with the fervour of an addict), even the amusing friendly rivalry between Legolas and Gimli. Foremost of the characters, however, is the world itself, described in relentless but glowing detail.

The overall story may be more densely packed with characters, and follow more of an extended narrative, than the more swords-and-sorcery offerings in the Appendix, but it’s also more rewarding for it. And compared to modern fantasy sagas, it’s tiny, taking up about the same number of pages as a single book in the Wheel of Time or Song of Ice and Fire sagas.

Inspirations

Tolkien has a strange place in terms of inspirations. The elves, dwarves and orcs follow Tolkien the most closely than other fantasy/folklore iterations. Halflings, treants, and the Balor demon are product-identity dodging hobbits, ents, and Balrog respectively. Arguably, giant eagles, the werebear, worgs, giant spiders, stone giants, and wights all get their inspiration from Tolkien too (but could equally come from the same kind of folklore). And the Ranger class, of course, is clearly inspired by Aragorn (and Faramir); back in the 1st Edition when every level of a character class had a title, the Ranger class had a level called Strider.

And yet, the story is a terrible model for a D&D adventure; far too much need to railroad (see the DM of the Rings webcomic for more - its creator Shamus Young having sadly passed away). Epic Quests are fine, but it’s the swords-and-sorcery stuff that plays more like a D&D game. Adventurers are usually more Conan, Kyrik, Cugel, Fafhrd or Grey Mouser than they are Frodo and Sam. The success of Lord of the Rings spawned endless trilogies of quests against a Dark Lord (Shannara, for example), and most don’t come close. Tolkien also brings a massive amount of lore to bear behind his writing which, as a DM, is not always advisable – it's a lot of work for little gain. Better to have dabs and dashes of lore rather than worry about having languages and poems and history and onomastic myths fully mapped out for everything; you’d kill yourself.

As stories, though, they reward close attention.

Comments

Post a Comment