Dr. Simon Reads Appendix N Part Eighteen: Michael Moorcock

This is an ongoing sporadic series, in which I explore classic fantasy and science fiction works. Appendix N is the bibliography of Gary Gygax's original Dungeon Masters Guide, and lists a range of classic SF and fantasy authors that influenced his interest in the fantastical. See the first part of this series for more information.

Michael Moorcock

Therefore I’d heard of Elric, and Stormbringer, and Melniboné, and The Eternal Champion, through such works as these, and the Stormbringer RPG from Chaosium, and also in parodies found in the pages of White Dwarf, from the satirical fiction of Dave Langford through to Eric of Bonémaloné in Carl Critchlow’s Thrud cartoons, but it took me a while to eventually get round to reading any Moorcock.

Not least because … where exactly do you begin? Well, the Appendices suggest the Elric stories, and the first Hawkmoon trilogy. Which leaves off the second Hawkmoon trilogy, the two Corum trilogies, and the Erekosë trilogy, as well as all the Jerry Cornelius stuff, End of Time cycle, etc., etc., etc. And unlike the other aspects of the Eternal Champion, the Elric stories don’t match story chronology with publishing chronology, plus to add confusion sometimes the stories, and the collections of stories, are reprinted and re-titled.

I read the Hawkmoon books ages ago, as well as the second of the Corum trilogies (being, as I was at the time, limited to what existed in the local public library). Here, for the first time, I will also be tackling the Elric stories.

Elric

One problem that a reader can have with the Elric stories compared to the other aspects of the Eternal Champion is that, much like the Conan stories, they were published not only piecemeal in various places, but also not necessarily chronologically in the protagonist’s timeline. Not only that, but Moorcock would return to the stories and revise them, and they’d then be renamed and published as part of many different anthologies. Fortunately they’ve now been compiled by Gateway publishing into a sequence of seven books, more or less bringing all of the works into an ongoing saga.

In Elric of Melniboné we are first introduced to Elric, the Dreaming City of Immryr, the Young Kingdoms and the decadent Melnibonéan race, a crumbling remnant of a once great and still feared race of people beyond human, tamers of dragons. Although Elric is unique in his albinism, one can’t help but wonder of George RR Martin based his Valyrians and Targayreans on the Melnibonéans. White-haired, lost kingdom, incestuous, cruel, dragon-riding? Check every time!

Elric is also unusual among his people in that he exhibits empathy, and is the only one who seems to see that his people are no longer great but need to adapt to modern times. As such, he ends up being usurped by his cousin Yrrkoon (or maybe Yyrkoon, it’s easy to get lost with Moorcock’s double letters and apostrophes) who also puts Elric’s lover Cymoril (Yrrkoon’s sister) into an enchanted sleep. We follow Elric’s quest for the fabled sword Stormbringer to defeat his cousin and although Yrrkoon wields Stormbringer’s twin, Mournblade, Elric prevails, but then hands the throne to Yrrkoon as regent while he goes off to explore the world in search of a way to save his people.

This pretty much sets things up to come.

The Fortress of the Pearl is a much later work, written in 1989 whereas most are 60s-70s. Here Elric, winding up in a distant desert land in his wanderings, ends up on a quest through the dreams of a young princess trapped in an enchanted sleep (mirroring Cymoril) with the aid of a “dream-thief” in search of the titular pearl at the behest of a decadent noble who has blackmailed him into accepting the task. Although the setting is one of an everchanging dreamscape, with typical Moorcock notes of psychedelia, Elric here fulfils pretty much the standard hero trope and here he could largely be replaced with Conan or Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser without too much difficulty.

Which brings me to a side observation. Elric is sometimes described as being an “anti-Conan”; he’s pale, thin, and requires either drugs or Stormbringer to maintain his strength, but in many ways he still follows the fantasy hero tropes. Despite his supposed frailty Elric is still a skilled swordsman and usually prevails in his fights. Some time back, possibly reviewing the Kyrik and Kother series, I wished for a protagonist with a bit more introspection, and we do get that with Elric; he is, at least, more of a poet and philosopher than the barbarian heroes, even though he still tends to move forward with action all the time.

Thinking about it, the most deliberate opposite to the typical fantasy hero is in Stephen R Donaldson’s Chronicles of Thomas Covenant (not an Appendix N entry). Donaldson has Covenant, a man afflicted by leprosy and lacking two fingers on his right hand, refuse to believe in the fantasy land where he is transported, and refuse to accept his role as “chosen one”. Not only that, Covenant is a physically incapable man. Although his wedding ring is a source of great magical power because of the white gold it is made of, Covenant is not an athlete or a swordsman, and his magic is dangerous to the world if he uses it. Thus for most of the first trilogy, he is a troubled bystander to events. By the time of the second trilogy, he spends much of it neutralised or comatose. For much of the third he is believed dead. Added to this an early sexual assault and he about as far from the barbarian hero archetype as it’s possible to get. This isn’t for everyone and many find him either boring or reprehensible, but I rather like the stories, even Donaldson’s notoriously baroque descriptions.

But back to Elric, who I would say falls somewhere between Conan and Covenant.

Book Three of the Gateway collection is A Sailor on the Seas of Fate, which contains three stories made into that particular collection (two of which are revisions of earlier stories), what was once The Weird of the White Wolf (which features the earliest Elric story The Dreaming City) and some other stories dating from 1961 to 2003 including While the Gods Laugh and The Singing Citadel.

The Dreaming City forms the crux of the tale, where Elric returns to Melniboné at the head of a fleet from The Purple Towns led by his friend Count Smiorgan Baldhead. Here, Melniboné is laid to ruins, but Cymoril dies on the point of Stormbringer and most of Elric’s Purple Towns allies are destroyed. Moorcock cites Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword as an influence on Elric, and this is evident; the inevitable doom and the black-bladed sword; but here it all seems more perfunctory whereas Anderson (and Tolkien, in the Silmarillion) manage to capture the steady and gradual march of calamity towards the protagonist.

The three volumes of the Sailor on the Seas of Fate proper are again visitations to other realms and somewhat dreamlike. It begins with Elric joining other incarnations of the Eternal Champion in a quest for Tanelorn, a story revisited from Hawkmoon’s point of view in The Chronicles of Castle Brass. Other episodes are again somewhat Conan-esque – strange islands, pirates and wily sorcerors, all told with a more 1960s sensibility.

Moving on to The Sleeping Sorceress, we see Elric pursuing his most notable nemesis, the Pan Tang sorcerer Theleb K’aarna. Accompanied by Moonglum, another aspect of the Eternal Companion, Elric first encounters the eponymous sleeping sorceress Myshella before going on a series of adventures culminating in a quest with Corum and Erekosë to find one version of Tanelorn in order to save another. And compared with another Erekosë story in the same collection, it becomes clear that Erekosë is the most protean of the aspects of the Eternal Champion. Here he is a large black man, in the other story he is thin and blond.

And here it should be noted that The Sleeping Sorceress collection contains other story fragments, including one called Sir Milk-and-Blood where it appears the Elric survives to the modern day, where he deals a “reward” to two men who have blown up a tram (reading between the lines, they are IRA or some other Irish paramilitary). Is this part of the Elric timeline or not? Reading other Eternal Champion tales, this story apparently forms part of the Von Bek cycle.

Here, reading the Eternal Champion stories becomes a little like the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Each hero has its own story, but they all interlink, and when they combine forces occasionally the reader gets more out of it if they have been a completist about all aspects. And in many ways it is like the MCU phases as well. Certainly the multiverse aspects of the Eternal Champion tales are like Marvel Phases 4 and 5, but there’s also a growing theme throughout of the battle between Law and Chaos, and the role played by the entity that is Stormbringer and/or the Runestaff, much like the Infinity Stones storyline through Phases 1-3.

Elric’s final outing is in the full-length novel Stormbringer!, where all of what has gone before comes together in a climactic and apocalyptic story where Elric and his friend Moonglum face no less than the complete un-making of the world by the forces of Chaos, and here we see hints of how the Young Kingdoms eventually become our world as they are wiped away to be replaced by a world with more Law and less Chaos. And here the nature of Stormbringer is (more or less) revealed as an independently-minded agent of change.

Broadly, the Elric tales fall into a number of stages. The first is where Elric is still a prince of Melniboné, culminating in his destruction of Immryr and all that he holds dear in The Dreaming City. Next, Elric is a landless wanderer, seeking a way to forget and perhaps self destruction, before he then falls into the ongoing series of antagonism with Theleb K’aarna. Eventually Elric finds a kind of peace with his wife Zarozinia, and a friendship with Rackhir the Red Archer, protector of the peaceful city of Tanelorn. Throughout this, there is a growing threat from the Lords of Chaos, and this comes to its climax in Stormbringer! where Elric’s story comes to its inevitable end.

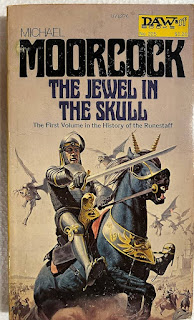

The Hawkmoon stories are more straightforward, existing as a quadrilogy (The History of the Runestaff) and a sequel trilogy (Count Brass). The appendices only recommend the first series (and oddly, in the original Appendix N, only the first three).

The setting is a far-future one, not dissimilar to that of Lin Carter’s Gondwane series, with trappings such as ornithopters and strange machines on top of the usual fantasy tropes, and names stemming from things from our era (notably the Dark Empire of Granbretan). The forces of Granbretan dominate the rest of the world through cruel animal-masked rulers and their god-emperor Huon who lives suspended inside a crystal sphere of life-giving liquid. The main antagonist is Baron Meliadus of Granbretan, an ambitious nobleman and personal nemesis to Hawkmoon.

Hawkmoon, and his friend Count Brass, hold out against the forces of Granbretan much like Asterix the Gaul’s village against the Romans, and the stories mostly follow fairly typical Moorcock narrative of quests for various McGuffins, most of which give the titles to the last three volumes The Mad God’s Amulet, The Sword of the Dawn, and The Runestaff. Hawkmoon and friends travel across the future world with a variety of adventures similar to Elric’s wanderings – get this object to solve that problem, and so on. Like other aspects of the Eternal Champion, Hawkmoon has a debilitating condition, in this case the eponymous Jewel in the Skull, a black jewel implanted by Baron Meliadus to ensure his loyalty, that will destroy his brain if he disobeys. However, whereas Elric has a love-hate addiction to Stormbringer, Hawkmoon is able to get the jewel deactivated quite quickly.

There are lots of fun ideas in these stories, like the mysterious ruins of Dnark (New York), ornithopters, and the twisted forces of Granbretan, although the characters are all a little flat.

The sequel trilogy – Count Brass, The Champion of Garathorm, and The Quest for Tanelorn are not given as recommendations but are worth a read. They do somewhat undermine the deaths at the end of The Runestaff, but are interesting. The Quest for Tanelorn overlaps with one of the Elric stories in Sailor on the Seas of Fate, seen in this case from Hawkmoon’s perspective.

Themes, Notes, and Other Maunderings.

Moorcock gradually builds up his setting of a multiverse where the Cosmic Balance oversees the struggle between Chaos and Law, where the Eternal Champion appears time and again in many guises, and where also there are parallels of the Eternal Companion, and where the character Jerry Cornelius appears many times, as Jhary-a-Conel, Jehamia Cohnahlius, etc. Moving through the world is the mysterious entity behind Stormbringer, which in one of the Von Bek stories may also be an avatar of the Cosmic Balance (even though Stormbringer itself is of Chaos), and may be the same as, or related to, the Runestaff. What is quite nice is the ambigiuty, Moorcock himself never tells you outright but leaves clues for the reader.

His writing style breezes along nicely, and most stories are quite short – Moorcock himself often completing a book in a few days. Consequently, however, the plots tend to be quite rudimentary with the characters lurching from one encounter to the next, a lot of repetition of seeking a magic artifact to solve a problem, and a tendency for deus ex machina. The Elric stories, in particular, suffer from Elric suddenly recalling how to summon up an elemental or animal lord which appears and fixes his problem. That said, Moorcock has some great inventiveness; he’s a little like Neil Gaiman in that the ideas are often better than the stories in which they inhabit. Which makes him a good source of things to use in RPGs.

From interviews and letters published in these collections, and in Imagine magazine, we learn that Moorcock admits influence from other authors in this series, especially Poul Anderson, borrowing both the idea of Law and Chaos from Three Hearts and Three Lions, and of course the doomed hero with cursed sword motif from The Broken Sword. He does, however, manage to develop these further and make them his own. Whereas Chaos in Anderson’s story is essentially the power of evil and tyranny, in Moorcock’s setting it is as much a necessary force for change, while Law can become too restrictive. Hence the existence of the Cosmic Balance between the two. And if we compare the Young Kingdoms setting of Elric and the Tragic Millenium setting of Hawkmoon, we find one setting more steeped in Chaos and another in Law, but in both cases ironically the Eternal Champion more closely serves Chaos (Elric) and Law (Hawkmoon) to overthrow the dominant power and restore balance. Is there a theme here, perhaps, of fighting fire with fire? Of the powers being used against themselves being more effective than the opposite power. Maybe.

Inspirations and Influences

Moorcock is largely happy for others to use his works, and gladly allowed the use of the Melniboné Mythos in the original print of Deities and Demigods. It was removed in this case not because he requested, but because Chaosium bought the license to produce the Stormbringer RPG (and later also a Hawkmoon RPG). Notably, the Melniboné Mythos section has 40 different entries, Nehwon 35 and the Cthulhu Mythos merely 17, which I think demonstrates both the fertility of Moorcock’s imagination and the ease of which his ideas can be inserted into an RPG setting. Moorcock also provided the idea (but not the gaming gubbins) for a scenario in Imagine Magazine Issue 22, a an Earl Aubec tale called Earl Aubec and the Iron Galleon.

The most obvious influence is the presence of Law and Chaos in the alignment chart, and although the D&D version feels different, it is still closer to Moorcock’s version than Anderson (which is closer to Basic D&D or the 4th Edition version). One can see the influence of Stormbringer itself on the Sword of Life Stealing, as well as the specific blades The Sword of Kas and Blackrazor (from White Plume Mountain). Beyond that, I’m not sure any specific elements of either Elric or Hawkmoon make it into the heart of the game. Moonglum, perhaps, is another influence on the style of the Thief character class, as well as Grey Mouser. As with most of the other books in this series so far, the influences are more thematic than specific.

Comments

Post a Comment